|

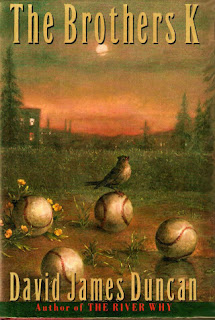

| Awareness looking out at nothingness through a baseball diamond. |

This last week I discussed George Sheehan's theory of defense and character in conjunction with The Odyssey, Homer's classic. Today I'd like to extend that discussion with another book on defense, Chad Harbach's THE ART OF FIELDING.

Baseball has its human universals, and the best baseball novelists sometimes use classic novels as referents to anchor their works. The prime example is David James Duncan who used Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov so well in The Brothers K. Michael Bishop used Mary Shelly's Frankenstein in his rather brilliant baseball novel, Brittle Innings.

Harbach, too, has his classic allusions in here to Herman Melville's Moby Dick, and also to Eugen Herrigel's Zen In The Art of Archery, John Irving's A Prayer for Owen Meany, D. T. Suzuki's Essays On Zen Buddhism, among several others.

THE ART OF FIELDING is a charming work, beautifully written. It made my best-of books last year, as baseball novel of its year. Among other things, it is a coming-of-age tale, a college novel, and a stylized Zen parable, the protagonist keeping a book within the book as a guide, Aparicio Rodriguiz's "The Art of Fielding," reciting its precepts as tale unwinds:

“The shortstop is a source of stillness at the center of the defense. He projects this stillness and his teammates respond.”

“To field a ground ball must be considered a generous act and an act of comprehension. One moves not against the ball but with it. Bad fielders stab at the ball like an enemy. This is antagonism. The true fielder lets the path of the ball become his own path, thereby comprehending the ball and dissipating the self, which is the source of all suffering and poor defense.”

“There are three stages: Thoughtless being. Thought. Return to thoughtless being. . .Do not confuse the first and third stages. Thoughtless being is attained by everyone, the return to thoughtless being by a very few.”

“Death is the sanction of all that the athlete does.”

All of which, well disguised, go into the book's design. There are three stages of the book, roughly as in the zen-like adage above. First there is a mountain, then there is no mountain, then there is. Or, there is the mindless grace of offense, then troubled defense, then the informed grace of offense again.

Henry's grace of play sends him into an ascending arc toward baseball stardom. The trouble comes suddenly when he kills Owen, sometimes known as the Buddha, with an errant throw. Owen only seems dead but he is still alive, of course, because you cannot kill the Buddha.

The karma resulting from this causes all of the main characters to back up and take stock. You might say they go on defense, fielding what life has thrown at them in an effort to salvage relationships. They come face-to-face with loss, with their temporal state, with ultimate nothingness. In the end, they arrive at a more mindful level of grace.

You might read the entire book and see very little Zen in it, but it's there all right. Pella says she wants the Chinese character for nothing tattooed on her ass. Henry's name for his glove is Zero. He finally reaches the brink of awareness on page 421: "Every day was just that: a day, a blank, a nothing, in which you had to invent yourself and your friendship from scratch. The weight of everything you'd ever done was nothing. It could all vanish. Just like this."

Baseball, like reading about baseball, is a pastime, a subliminal denial of death. The difference between the first and third stages is an awareness of the temporal nature of existence that cannot be learned from a book or taught in school. It can only be gleaned from experience and an inexpressible individual epiphany, a personal glimpse of transcendence. Which is why Henry goes on about the inadequacy of words.

Harbach is not the first to connect a stylized zen with baseball. George Plimpton, with the help of Pulitzer Prize-winner and buddhist Peter Matthiessen, wrote a comic baseball novel with a buddhist protagonist (The Curious Case of Sidd Finch, 1987). David James Duncan wrote "The Mickey Mantle Koan."

In Baseball and Philosophy: Thinking Ouside the Batter's Box (edited by Eric Bronson, 2004), there are several essays that touch on buddhist thought, including Gregory Bassham's "The Zen of Hitting." And just last year, former slugger Shawn Green came out with The Way of Baseball: Finding Stillness at 95 MPH.

_____

Addendum: A note about nothingness.

Nothingness is not as simple as some people seem to think it is. In the abstract, there is a calculated nothing, then there is nothing beyond the laws of math, nothing with the zero removed. Also, if a void contains a potential or an algorithm for something, it is not nothing.

I believe that the spiritual is something other than the material, that the spiritual is something else, bits of spirit having a physical material experience, alien here. I might be wrong about this, but I don't believe that the evangelical atheists have it nailed down either.

While I'm always interested in reading anything new by such true believer atheists/materialists as Lawrence M. Krauss, Richard Dawkins, and the late Christopher Hitchens, thus far I find all of their arguments either unconvincing or irrelevant, a preaching to the choir--unless you happen to be a fundamentalist. And I don't think that fundamentalists bother to read them.

As I've said many times, I don't agree with the buddhists about suffering either. As Marcus Aurelius pointed out, life is a gift and we should all live it as if it were a thing borrowed, and we ought to be willing at any time to give it back, saying--here, I thank you for this life which has been in my possession.

Love, empathy, kindness, and gratitude. The way to live.

No comments:

Post a Comment